Suppliers and consultants regularly make recommendations to their client companies. In many companies, these suppliers of products and services are trusted advisors, often having the responsibility of making a final decision on a project. Even with best intentions, however, the supplier’s decision of what is right for the customer is a difficult decision because there is a potential conflict of interest. The supplier has something to gain as a result of the decision if it recommends that its services or products are included as part of the recommended course of action. The monetary value and type of transaction may determine the severity of the conflict and the course of action that should be taken to deal with it, but in each case the clear potential for a conflict of interest requires a thorough comparison of potential benefits and costs for each party.

Consider, for a moment, how similar matters are treated by the law in relation to positions of trust. The law requires that a person who advises or acts on behalf of another must act in the best interest of the other person. In sales and consulting, there is certainly not an equivalent legal duty to a potential customer, but there is an ethical duty along the same lines. This conflict of interest comes into play in many scenarios. If you are a consultant billing on a long-term project and you discover that there is software that will do the same project for a much lower cost for your client and complete it much quicker, what do you tell the client? Similarly, if you are from a software company, and your software fulfills most of the client requirements, but not all of them, how do you approach the project? How do you rationalize the loss of personal income, billable hours, or an opportunity for your company with the benefits and value to your customer? There are criteria to help you evaluate whether you have a conflict of interest, and some suggestions for making your input as unbiased as possible.

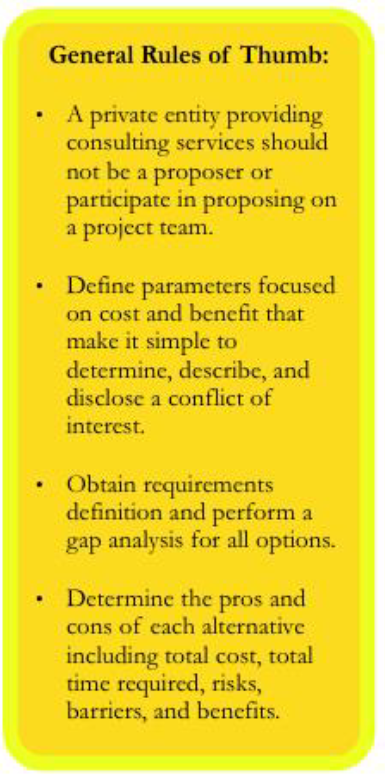

The first principle for properly addressing these ethical questions is to remember that your primary duty is to your client. The discipline of obtaining a requirements definition and performing a gap analysis among all the available alternatives is necessary to determine whether or not a product or service is optimal for a client project. Benchmarks or parameters should be defined in order to provide the framework for a systematic method of determining, describing, and disclosing a conflict. Parameters should include costs and benefits to each party involved in the transaction in the forms of capital, personnel costs, time requirements, risks, and any other relevant costs and benefits.

There are three major points of potential breach of ethical duty for a supplier of services or products:

- Failure to disclose a conflict of interest.

- Failure to accurately describe the extent of the conflict.

- Deliberate or knowing use of bad or questionable judgment.

There is the most risk of a conflict when the benefits to supplier and the difference in the comparative cost to the client are very high. In such a case, the supplier is most likely allowing his or her own interest to interfere with the best interests of the client. In a consulting situation, often the service provider is compensated with bonuses and commissions that are heavily weighted on billable hours and utilization, so a software product that effectively reduces the compensation to the consultant is spurned. In the case of a software supplier, the tendency is to claim functionality that is not a standard part of the packaged software just to make the sale or to ignore gaps that the software does not address. In those cases, the costs to the client escalate in relation to the work needed to fill the gaps not covered by the software that were not disclosed by the software supplier in promoting the sale. It is easy to see how each party could be financially motivated to sell its own product or service, even when careful assessment clearly indicates that such a product or service is not the optimal solution for the client.