There are few things that generate excitement and speculation like the announcement of a business combination. Almost without exception, the management promise of every merger and acquisition is to increase stakeholder value. However, it seems that this is not what typically happens. As evidenced by a 2019 survey by Deloitte, 40 percent of survey respondents say that half their deals fail to generate the value they expected at the onset of a transaction. It begs the question— what is going so terribly awry? More importantly, what must be done to ensure that M&A deals do in fact deliver the maximum value possible? This article is meant to answer both of these questions.

Inspired by the teachings of Adam Grant in his book “Give and Take”, it is important to understand that companies which focus on what they are going to get from an acquisition are less probable to succeed than those that focus on what they have to give it. Chances for the success of an acquisition can be increased by the acquirer in 4 ways: by being a smarter provider of growth capital; by providing better managerial oversight; by transferring valuable skills; and by sharing valuable capabilities. Let’s see how this is done.

Sources of Value and Causes of the Destruction of Value—The Value Gap

Shareholder value is measured as the increase in stock value associable with the merger. Because, rationalized, stock value is reflective of long-term earning capacity of the company, a proxy for increased shareholder value is the net present value of increased cash flow due to merger synergies.

The hope is that shareholder value will be increased by cost reductions achieved through economies of scale, the combination of duplicate corporate functions, and streamlined sales forces; capital efficiencies achieved through rationalized assets and the combination of duplicate facilities; and revenue enhancement affected though product development synergy (new products), shared marketing skills, and combined distributions.

The expected increase in value, while often achieved to some degree, is largely offset by situations that occur during integration. This produces what is called a Value Gap. Some major things that contribute to the Value Gap include:

- Integration issues

- Inexperience

- Lack/loss of vision

- Management wars

- Culture clashes

- Failure to manage risk and change

- Bad communication with stakeholders

- Prices rise, quality falls, customers leave

- Alliances and supplier relationships degrade

- Key people leave, and business continuity is lost

The result is the Value Gap — the unhappy coincidence of achieved value offset by unanticipated challenges, resulting in less shareholder value from the merger.

In addition to the Value Gap, there can be synergies after the deal is made that can add energy, creativity, and enthusiasm for new opportunities. This is referred to as Emergent Value, and it can help offset the Value Gap. Stemming from unanticipated synergies, Emergent Value is created by taking advantage of complimentary resources at all levels, finding more profitable uses for assets, achieving both strategic and operational fit, discovering new market opportunities, and selling products to existing customers. In addition, reinventing processes, shedding obsolete practices, and capitalizing on the creativity and excitement evoked as new colleagues interact, can play a role in generating Emergent Value.

Transition—the Critical Period

Most executives would be quick to point to a lack of synergies, an unrealistic vision, or an outrageous premium price for the reasons a business combination fails to deliver value. While these factors can certainly sabotage the success of the combined entity, even the best structured business combination can be sabotaged by another pitfall—poor post-merger integration (PMI). It is PMI that can most often lead to the Value Gap, but it can also provide opportunities for the creation of additional value.

In simple terms, a business combination can be considered to have two phases— the Transaction Phase (making the deal) and the Transition Phase (post-merger integration).

The Transaction Phase is the sexy part during which the deal is negotiated and then announced. The results of this phase are largely a function of deal-making negotiations. Typically, unless there is a big surprise during the post letter of intent due diligence, the financial structure of the deal is set.

The part which gets less attention is the Transition Phase, or the post-merger integration (PMI). This is the phase during which the disparate companies are integrated and combined. Very little attention has been given by business thought leaders toward addressing the challenges of post-merger integration. In an article in the Journal of Organizational Dynamics, business scholar Marc Epstein, PhD, states that “it is the actual execution of the merger strategy through the pre-merger and post-merger integration that appears to have the least understanding.” A focal point of this article is to address some of the most common areas of PMI/transition misunderstanding.

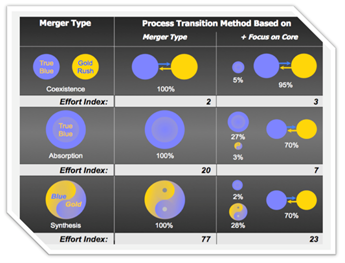

First, it is important to understand that not all mergers are the same with regard to effort. As shown in Figure 1, the intended result of the merger has a significant impact. If the intent is that the companies should continue to function largely autonomously after combination, this is referred to as coexistence.

If one of the companies is going to be absorbed into the operations of the other, this is referred to as absorption. Finally, if the disparate portions of the two companies are to be fully integrated, intending to keep the best of both, resulting in one better company, this is referred to as synthesis. These three types of results are achieved with sequentially higher levels of effort, with less effort for a coexistence, typically just needing changes to financial and managerial reporting and minor integration, more for an absorption, as the surviving entity’s systems supplant those of the absorbed entity, and a significantly higher level of effort needed to cull the best of both companies and integrate together.

Regardless of the type of merger, the transition time frame available to create value is short.

After the transaction and deal close, the next six months are critical. Leading up to the close and day one of the transition period, 40% of the changes that will ever be initiated are set. This, of course, includes the changes mandated by the structure of the transaction agreement. At 3 months 65% have been initiated, and at 6 months 85% have been initiated. The remaining 15% of initiatives must build on those of the first six months. At around six months, for better or worse, the newly formed company settles into a steady state. Because the timeframe is so short, the way the transition is managed is critical.

Three Ways to Manage a Transition

There are three ways to manage a transition: Too Little, Too Late, and Just Right.

Too Little

Because deal-making is the cool, high-profile phase of a merger or acquisition, and there is a misconception that a good deal guarantees a successful merger or acquisition, there is a temptation to limit the transition effort to the day one hoop-la. This is a mistake. According to Kenneth W. Smith of Mercer Management Consulting, “The deal is won or lost after it’s done.” The short attention span of the “Too Little” approach can result in the transition team feeling abandoned and disincentivized, resulting in confusion and paralysis, disintegration, and arriving at the six-month steady state with a large Value Gap.

Too Late

In this scenario, top management puts all their attention into closing the deal, but interest ebbs after the closing. They fail to impart their vision, knowledge, focus, and momentum to transition management. Transition-phase visioning, planning, and organizing do not start until the deal is closed (or they never occur at all) as the transition teams rush into action. Furthermore, events race ahead and are out of control—losing customers, key employees, and shareholder value in the chaos. Time, money, and energy are burned in firefighting and fixing mistakes. In the “Too Late” scenario, the momentum for a good transition begins to ebb even before the close, and then after close the transition effort is a rush to catch up. Without a clear vision from management, the transition team is at best guessing what needs to be done, resulting in continual undoing, redoing, and repairing. The result is reaching the six-month steady state with mixed results.

Just Right

In this scenario, management begins the transition effort almost immediately after the letter of intent is signed. By planning and lining up resources early and communicating a vision and plan to the transition team, by day 1 the transition is fully under way. By properly handling the transition effort, it is clear to all parties that the transition effort is to be taken seriously: it receives adequate resources; planning is an integral part of transaction due diligence; the transition team is fully engaged and ready to go on day 1; the best people from both companies design the new company; a rapid implementation reduces the cost of the transition; and the design of the processes allows the team to seize opportunities for synergy to emerge and persist. The result is reaching steady state while avoiding the Value Gap and having created emergent synergies.

Key Success Factors of the Integration Process, helpful in avoiding the value gap and maximizing the possibility of achieving emergent synergies, are proactive integration along with maintaining speed and momentum.

- Proactive integration, which means planning, monitoring, and adjusting how the integration process is being affected to maximize value, requires treating the transaction and transition as a single unified process, relying on experienced and trusted leadership, having a well-defined vision and focus, and provisioning adequate resources.

- Speed and momentum are critical, and it is important to stay ahead of events, strive to realize merger value early, take quick action on people issues, and sustain energy and enthusiasm.

Vision and Plan: Hit the Ground Running in the Right Direction

Vision—The Transition Plan

Using a top down perspective, key to ensuring a successful transition is establishing and communicating the goals of the merger—the future state and the value it will deliver.

Then a Transition Plan, an actionable program to focus the process of achieving the plan, should be developed. This program will include:

- Tasks (changes and deliverables) required to complete the plan; teams and people who will design and implement the future state; and resources, the tools, and the facilities the teams will need.

- Targets (measurable milestones toward realizing the value), which should include accountability in the form of personal and team responsibilities for hitting targets and incentives, and rewards for hitting targets.

- Priorities (critical tasks and targets for attaining the value) focusing on the tasks that create the highest value, understanding that even in the best plan, resources are limited, and choices must be made.

- Finally, Change Mechanisms, methods and manners by which unexpected opportunities can be seized and surprise problems can be addressed.

In addition to the Transition Plan, related but discrete, it is important to establish a Process Plan, a People Plan, and a Technology Plan.

Each of the Transition, Process, People, and Technology Plans must support the achievement of the vision and the value it promises. The following are the Why, How, and What questions that should be asked when developing these mutual, vision-supporting plans.

Why? Key Business Strategies and Synergy Opportunities:

- Why are we merging?

- How will we know that we are successful?

- What are our integrated operational strategic goals?

- How will we consolidate to achieve maximum benefit from both organizations?

How? Management Philosophy:

- What kind of culture/employee environment will we build and foster?

- What type of management style will we employ?

- What strengths of each organization will we leverage?

- What weaknesses will we overcome with the merger?

- What policies should we adopt?

- What new policies must be developed?

- What skills do we need to retain and develop?

- What should our culture characteristics be?

- What initiatives should we continue or halt?

What? High-Level Business Operating Model:

- How will we manage our key business processes?

- What is in scope?

- What are our product, market, and channel strategies as well as our desired core competencies?

- How can each function or process contribute to achieving the merger objectives?

- What must happen to integrate each process?

- What will the integrated process look like?

- What will the integrated organization look like?

- What skills and knowledge must we maintain?

- What will our systems and applications infrastructure look like?

- What systems must we roll out to enable the integration?

- What data and information must be consolidated or converted?

- How will we support our systems and users?

Processes—Designing the Synergies into the New Business

What needs to be done from a process standpoint varies on the type of merger.

For a coexistence, there should be a fast, cheap transition. At most, there is relatively minor work to impose control and coordination. That said, there may be unexpected incompatibilities, limited process synergies, little process improvement, little buy-in from employees, and no real economies of scale.

For an absorption, more effort is required, generally on a magnitude of 10 times the effort of a coexistence. The operations and assets of the absorbed company are just integrated into the existing systems of the acquirer. The best can be absorbed, the rest discontinued. This is not as easy as it sounds. The acquired operations and assets may not fit into the new organization well. Some strengths of the acquired company may be lost. The absorbed employees may not fit in well and might feel they have second-class status.

For a synthesis, even more effort is required because the purpose is to take the best processes from both companies. This can create unique challenges but provides the greatest upside potential for synergy. There are more emergent process-improvement opportunities. Because of the complexity of a synthesis, interim processes are needed during transition and there is a risk of losing focus and momentum.

Regardless of the type of merger, a key success factor is to Focus on Customer Processes. Priority should be given to customer-facing processes – Sales, Support, and Order Management. Design processes to present one consistent face to the customer. Deliver the benefits of merger synergies visibly to customers – new products, better service, more for their money. Create and staff interim processes to sustain the quality of products and services through the transition.

People—Realizing Merger Value by Getting the Best to Give Their Best

Clearly, a successful merger requires the higher motives to prevail at all levels of the organization – that is necessary.

Maslow defined three levels of human needs. The most basic are survival and must be satisfied before the higher levels are reached. In a business sense, the survival behaviors are those that people exhibit when they are concerned. A critical success factor is to minimize these survival type behaviors because they are destructive.

In a business context, the social level is demonstrated by company loyalty, feeling good about his/her job, their opinions are respected.

At the highest level, Self-actualization, the person is eager to go to the new world, is free from anxieties, and is able to develop emergent synergies, fulfilling others’ needs (not us and them).

On the Maslow hierarchy, employees acting from survival needs leads to fear and distrust, jockeying for position, rigidity and resistance to change, paralysis, distraction, collapse of productivity, resentment, sabotage, litigation, the best people resigning, and the worst people becoming resigned. These effects should be minimized.

Instead, an effort should be made to maximize the results of employees acting from self-actualization motivations. These lead to a sense of ownership of the new company; eagerness to contribute to the change; freedom to focus on new processes and systems; constructive criticism and input; being welcoming of new colleagues; generation of creative ideas; and discovering emergent synergies at all levels.

In addition to focusing solely on existing employees, thought should be given to the possibility of using external resources during the transition. By bringing in people from the outside, a company can:

- Fill in-house gaps in merger transition experience

- Ability to manage the business’ ability to manage a merger

- External experts can develop in-house merger capability

- Use an independent, external firm specializing in merger integration

- Avoid conflicts due to other services from the same provider

- Independent firm can select best providers of extra services

- Overcome the double resource crunch of a merger transition

- Enough competent people to accomplish the integration

- The right people to keep the business humming through the transition

- When they’re done, they’re gone

- Leverage purchase accounting to pay for the transition

- Transition costs don’t drag down the operational bottom line

- Transition achievements become permanent, reusable operational improvements

Technology—Enabling the New Enterprise without Delaying the Transition

Disparate and discrete data and information systems are a significant hurdle in the integration process. The key success factor for technology enablement in a merger entity is to plan technology integration from the top down, looking to the requirements of the business both from company leadership as well as employees at all levels. Technology should be aligned first with the leadership’s vision of what the company should be doing, and then to the employees, providing the needed knowledge and the power to get things done. Planning should be done from the top down, but the key success factor for the implementation is to implement technology integration from the bottom up. Implement the plan by addressing change needs as they relate to networks, computer systems, storage, and other machines. Then connectivity, data, and applications should be addressed.

As an example, take just one area of technology – but a central one – data integration. Integrated processes require integrated data. Focus data integration effort on processes that will be combined by absorption or synthesis. Processes that merely coexist don’t need integrated data. All those who participate in an integrated business process must have common definitions for all of the people, policies, and procedures that they deal with. Data should be consolidated into shared, non-redundant data stores. Hardware infrastructure must be up to handling the combined quantity of data with adequate performance.