Data protection and security protocols have become more robust in the last two decades. This has been driven both by increasing incidents of data breaches – statutorily acts such as the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the Gramm-Leach- Bliley Act, Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITEVH) Act, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), and the Fair and Accurate Credit Transactions Act – and by the Payment Card Industry Security Standard, to name just a few drivers. In general, most entities have implemented strong safeguards to ensure that issues such as inadvertently sharing identifying information with third parties and the existence of sensitive data (credit/procurement card numbers, tax IDs, social security numbers, vendor/customer bank account numbers, etc.) for their current and active data are addressed.

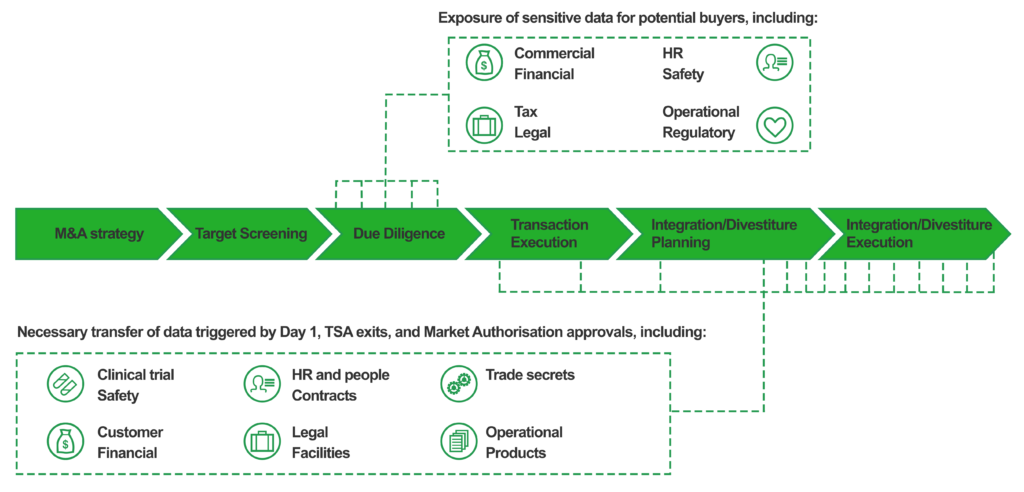

Though these measures have become more commonplace, the threat of cybercrime and data breaches is unfortunately still on the rise. Cybesecurity Ventures, a cybercrime magazine, estimates that cybercrime will cost approximately $10.5 trillion per year on average by 2025, up from $6 trillion in 2021. IBM estimates the average cost of a data breach for a company is $4.24 million per incident. This figure covers detection, containment, revenue loss and equipment damage, but there are also unspecified irreversible losses to the company’s reputation and goodwill. Even more worrisome during merger, acquisition, or divestiture activity is loss of intellectual property, the impact of operational disruption, and the costs of regulatory compliance. The below figure from Deloitte illustrates typical points in the M&A lifecycle that are dependent on data transfer, putting the involved companies at increased risk of cybersecurity threats:

These threats are more likely to arise when a company has legacy or inactive ERP data. Prior to the enhanced security protocols of the last two decades, it was common practice to put sensitive data into an ERP system’s unsecured fields, such as memo and descriptive fields, or in otherwise re-purposed fields. As a result, much legacy data does not meet privacy and security standards. This risk can be managed without having the expense of a hygienic data purge when the legacy data is buttressed by access controls. The biggest risk is when a third party is given access to or possession of either a portion or clone of an existing ERP instance. This most commonly occurs in divestiture or partial divestiture situations.

In fact, it’s been speculated that undergoing complicated large-scale business changes (like a divestiture, an acquisition or a merger) opens an enterprise up as an easier target for a security breach because of infrastructure changes and limited resource allocation. This is an especially vulnerable time because if a parent company creating a clone for their acquired company still retains the data of a (now sold) child company and suffers a theft or data breach, not only do they have the downfall of their own reputation, but they could be liable for damages to the child for the compromise (or vice versa), compounding the threat if that company in question is flipped again and purchased by another entity. If they have data belonging to the parent company, they are at risk if any of the companies has a breach that involves the parent company’s data. As companies are repeatedly bought and sold, a data breach can be very costly for both the acquirer (parent) and the acquired (child) company. Over time, the original source of the data is not clear, and the breach can have untold impacts and ever-increasing costs. The bottom line is that all parties will bear the burden, monetary expense of remediation, and opportunity cost of a damaged reputation.

There has been an uptick in the handling of divestiture and acquisitions by cloning the instance in question, masking the data and handing it off as part of the sale – but there are inherent risks for both the buyer and the seller when using a clone or masking solution for a divestiture. Companies who are creating a clone for their acquired company still have data belonging to the child company, and therefore, they would not only have the reputation of their own customers, but they will likely have to pay the child company compensation for breach of their data. The reality is that an experienced hacker can undertake an unmasking initiative, access that data by finding related data, or querying at the data base level, and open vulnerabilities for both an internal and external data breach.

With the exceptional dangers involved, it begs the question: why have these processes become commonplace? The seller risks inadvertently sharing trade-secrets or competitive advantage via sensitive information left in the database, and the buyer undertakes the complication of carrying the masked data that it does not own in their system, causing delays and increasing infrastructure costs (i.e. a larger footprint, additional license fees, added expense to manually segregate the data for reporting or compliance, etc.).

This risk cannot be understated. A single inadvertent unauthorized disclosure of private customer or vendor information could result in large penalties, sometimes into the millions of dollars. If the clone instance is provided to a competitor in a partial divestiture, added to this risk is the possibility of damage resulting from inadvertent disclosure of the non-divested business’ proprietary strategic information, such as vendor and customer credit lines, discounts, customer and vendor contractual details, etc.

Finally, to magnify these risks, the threat of litigation losses respective of inappropriate data disclosure can dwarf the costs of other risks.

So what is an appropriate risk management strategy to adopt during a divestiture? An entity has three choices: minimize the risk, accept the risk, or ignore the risk.

Minimizing the Risk:

This strategy involves a variety of steps, including non-disclosure agreements with third-parties, contractual obligation, and other due diligence around the risks. However, the ideal way to minimize the risk is to purge old/legacy non-divestiture related data from the clone instance provided to the divested or acquired entity.

Accepting the Risk:

Accepting the risk can be an effective risk mitigation strategy. However, to accept the risk, entity management must have a relatively accurate estimate of the risky data exposure accompanied by a what- could-go-wrong quantification of the potential risk respective losses.

Barring a means to quantify the risks associated with the divested clone instance’s legacy and non- divested entity related data, entity management is not accepting the risk. Instead, by default, entity management has chosen the riskiest approach – Ignoring the Risk.

Ignoring the Risk:

If an entity’s management cannot be provided with a reasonable estimate of quantified risks associated with the divested clone instance’s legacy and non-divested entity related data, then barring minimizing the risk by purging unrelated and legacy ERP information, management has chosen to ignore the risks. This is the worst possible strategy, because it leaves the entity open to the risk of being deemed negligent, which can significantly exacerbate litigation, business and other risks

In conclusion, during the rapid transition of a divestiture, it is critical to ensure that due attention is given to the risk of legacy, inactive, and unrelated to the divestiture ERP data. The best strategies are to either minimize or accept the risk and avoid the unacceptable act of ignoring the risk.